10.1.1 What is a draft?

Draft is the most popular format in a limited environment. The meaning of the word is ‘recruitment’ since the format is built on a selection of cards with the aim of building a deck that is as efficient as possible. At the beginning of the draft, each player receives 3 packs of 15 cards. The players open the first pack, choose a card from it, and pass the remaining cards to the left. The players continue in this way until there are no more cards left (at this point they will have 15 cards in their hand). Then the players open the second pack and continue in the same way, but this time they pass the cards to their right. With the third pack, they return to pass the cards to the left. At the end of the draft, each player will have 45 cards from which she must build a deck of 40 cards including lands. It follows that she will use about half of the cards she chose during the draft.

Figure 3: Packs rotation in draft[1]

In those early days, when Magic was a young game, players would occasionally play a sealed deck. The format wasn’t particularly exciting because it didn’t give the players a sense that they could express their skill in deck building. It was probably Richard Garfield herself who thought of a way to allow higher level synergy by using a limited number of packs. The draft format was born. The first drafts were in the revised set. Brian David-Marshall, who has been called the historian of Magic, told us in an interview how Richard taught her the new format and was the first to pass her draft packs…[2]

10.1.2 How do players choose their cards in drafts?

The first criterion for choosing cards in drafts is of course quality. However, this is not the only consideration, not even the main one. At drafts, players are much more focused on achieving functional synergy and sometimes even mechanistic synergy compared to other formats in a limited environment. The reason for this is related to the relatively large pool of cards from which the player can choose the tools she will use, compared, for example, to a sealed deck.

In the previous chapters we dealt with selecting cards according to criteria of quality and synergy, and there is no point in repeating this again. However, in the draft format there is a third criterion according to which the player chooses cards. Unlike a sealed deck (see next chapter), in a draft the players can influence the quality of the cards handed to them. They do this using two tools at their disposal: the ability to read signals and transmit them.

10.2 The art of signaling

The art of signaling is designed to get the player the highest quality of cards relative to the other players. However, using signals requires a certain cooperation between players sitting next to each other. This raises an interesting question: MTG, as we know, is a zero-sum game, meaning that an advantage gained by the opponent is a disadvantage for you and vice versa. There is no sense in trying to get good decks for everyone. If so, why would a player be interested in cooperating with his neighbors by sending clear signals? The answer is that players are interested in cooperation with the players sitting on their left in order to obtain a better quality of cards for both of them compared to the players further away. The fact that your neighbors also benefit from the cooperation involved in sending clear signals is the price you have to pay for improving your chances against other players further away. Another point on signaling is that even if you cooperate with your neighbor, you are more likely not to face them in the draft than facing them

10.2.1 The language of signals

The ability to evaluate cards accurately is used as a device for deciphering signals and communicating them clearly, since the common understandings regarding the quality of the cards is the language in which signals are transmitted during a draft. A player who is not proficient in this language cannot benefit from these signals. The fact that the players share a common understanding regarding the quality of the cards does not necessarily mean that there is complete agreement between them regarding the value of each card and its position in relation to the other cards. Professional players at the highest level often argue among themselves about how to evaluate a specific card. However, experienced players share an agreement regarding the approximate value of the cards, and this is enough to allow a ‘conversation’ to be conducted in the draft.

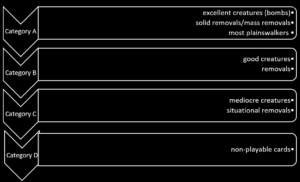

Let’s take a random set of MTG. We choose a certain color and give each card a score according to its valued quality so that we will have a descending list of cards, from the most valued to the least valued (we should set aside mythic and rare cards since their quality distribution is significantly different). Now we will divide the list into four equal parts. What we got were four seemingly arbitrary categories of cards. In fact, it is much less arbitrary than it seems at first glance and reflects a general tendency of various sets in MTG. Try it yourself and you will realize that the general trend more or less reflects the following division:

Category A: High-quality cards – cards that receive a particularly high score in the cost/benefit test. At the top of this group are bombs, cards that can alone contribute a lot to achieving victory, although not every quality card has to be of this magnitude. In general, these are very desirable cards that probably would not pass away in draft longer than the first few picks.

Category B: Cards that are playable – these are cards that receive a good score in the cost/benefit test (but not beyond that) and are therefore almost always included in the cards played in a deck.

Category C: Fillers – cards that do not score well in the cost/benefit test but are not so bad that they should not be used. Players prefer not to include these cards in a deck but are often forced to do so when there are no better options.

Category D: Non-playable – these are cards whose cost/benefit ratio is so bad that using them could significantly damage our position. Sometimes these are cards that play a role only in quite rare situations and are therefore highly situational, serving at most as side-board cards.

Now, in order for the players to be able to communicate with each other, they do not have to agree on the exact value of each and every card. They only have to agree among themselves about the category that a particular card belongs to. Later we will see how this categorical division can be used in practice. It should be added that the division into categories is in most cases intuitive. An experienced player knows how to assess whether a card is of high quality, playable or obviously unplayable.

Figure 4: Categories of cards

How can a player make use of signals in order to achieve better card quality than the other players? An operative answer to this will focus on two elements: (1) They must make sure that the colors they choose are chosen by the smallest number of players around the table; (2) They must make sure that their closest neighbors do not play the colors they chose or at least one of them. Now we will deal with each of these components separately:

- The number of colors played around the table

One doesn’t need to be a mathematician to understand that the fewer players to choose a certain color, the higher the quality of the card pool for those who choose this color, regardless of the position they sit in. To illustrate, let’s assume that in a draft of 8 players, all players choose 2 main colors, while half of them (4 players) choose a third color as a splash. If so, the players jointly chose a certain color 20 times. Now the question arises as to how this choice is divided between the different colors in the game. A completely equal distribution means that each color is chosen 4 times, that is, by 4 different players. However, distributions close to this number can also be considered equal distributions.

In order for a distribution to be considered unequal, at most two players will chose it as their main color and another player will use it as a splash. In this case this color will be considered underdrafted and choosing it will usually give an advantage in terms of card quality to those players who did so. Therefore, locating the less chosen color at the table increases the quality of the cards the player will be able to get his hands on.

- The location of the players who share a color with you

The quality of the cards that the player obtains depends not only on the number of players around the table who share the same color but also the position of these players in relation to her. Why? The reason for this is that the cards maintain a quality hierarchy between them, so whoever gets to choose first, gains more. Of particular importance are the first picks when the high-quality cards are selected. The further away the players who share a color with you, the more likely you will be to lay your hand on quality cards of the same color. For the sake of illustration, let’s say that you and the player to your right share exactly the same colors and that she is the one passing you the cards. In this situation, you cannot hope to win a category A card (except for the booster you opened) unless there was more than one such card in the booster that was passed to you, and, even then, you will win the one with the lower quality (here, disagreements between players regarding the quality of cards may result in both sides being happy). Yet if the closest player who shares a color with you is located three seats to your right, you could take control of the quality cards of the same color in three different boosters and this would give you a considerable advantage. In this context, it is important to remember that the neighbors sitting to your right are more important to you than those sitting to your left. This is because two boosters out of the three are moved clockwise and only one is moved in the opposite direction.

Gathering information is of great importance in drafts. Reading signals is a good way to collect information but requires skill and sometimes leads to wrong conclusions. There are those who prefer shortcuts. At GP Boston 2003, Trey Van Cleave was caught on camera peeking at his neighbor’s draft cards. she was immediately eliminated from the tournament.[3]

[1] draft-order – Card Kingdom Blog

[2] (457) Brian David-Marshall: The Magic Historian | Humans of Magic – YouTube

[3] Ensnaring Cambridge—10 Magic Cheaters Who Look Like Cats (hipstersofthecoast.com)